Structured Environments¶

The basic reinforcement learning formulation assumes a single entity in an environment, enacting one action suggested by a single policy per step to fulfill exactly one task. We refer to this as a flat environment. A classic example for this is the cartpole balancing problem, in which a single entity attempts to fulfill the single task of balancing a cartpole. However, some problems incentivize or even require to challenge these assumptions:

Exactly one task: Occasionally, the problem we want to solve cannot be neatly formulated as a single task, but consists of a hierarchy of tasks. This is exemplified by pick and place robots. They solve a complex task, which is reflected by the associated hierarchy of goals: The overall goal requires (a) reaching the target object, (b) grasping the target object, (c) moving the target object to target location and (d) placing the target object safey in the target location. Solving this task cannot be reduced to a single goal.

Maze addresses these problems by introducing StructuredEnv. We cover some of its applications and their broader context, including literature and examples, in a series of articles:

Beyond Flat Environments with Actors¶

StructuredEnv bakes the concept of actors into its control flow.

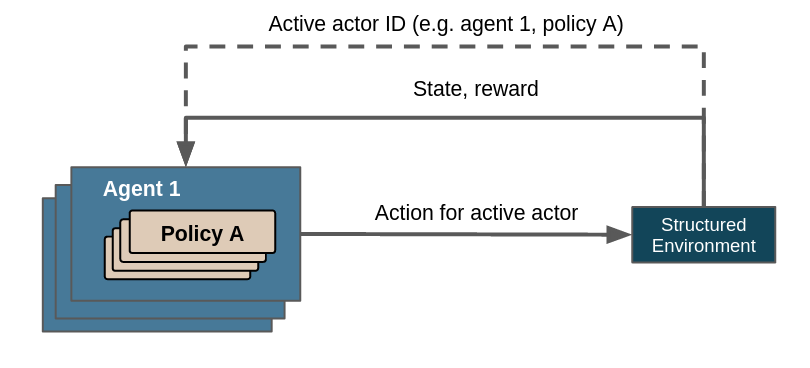

An actor describes a specific policy that is applied on - or used by - a specific agent. They are uniquely identified by the agent’s ID and the policy’s key. From a more abstract perspective an actor describes which task should be done (the policy) for whom (the agent respectively the acting entities it represents). In the case of the vehicle routing problem an agent might correspond to a vehicle and a policy might correspond to a task like “pick an order” or “drive to point X”. A StructuredEnv has exactly one active actor at any time. There can be an arbitrary number of actors. They can be created and destroyed dynamically by the environment, by respectively specifying their ID or marking them as done. Their lifecycles are thus flexible, they don’t have to be available through the entirety of the environment’s lifecycle.

Overview of control flow with structured environments. Note that the line denoting the communication of the active actor ID is dashed because it is not returned by step(), but instead queried via actor_id().¶

Decoupling actions from steps

The actor mechanism decouples actions from steps, thereby allowing environments to query actions for its actors on demand, not just after a step has been completed. The cardinality between involved actors and steps is therefore up to the environment - one actor can be active throughout multiple steps, one step can utilize several actors, both or neither (i.e. exactly one actor per step).

The discussed stock cutting problem for example might have policies with the keys “selection” or “cutting”, both of which take place in a single step; the pick and place problem might use policies with the keys “reach”, “grasp”, “move” or “place”, all of which last one to several steps.

Support of multiple agents and policies

A multi-agent scenario can be realized by defining the corresponding actor IDs under consideration of the desired number of agents. Several actors can use the same policy, which infers the recommended actions for the respective agents. Note that it is only reasonable to add a new policy if the underlying process is distinct enough from the activity described by available policies.

In the case of the vehicle routing problem using separate policies for the activies of “fetch item” and “deliver item” are likely not warranted: even though they describe different phases of the environment lifecycle, they describe virtually the same activity. While Maze provides default policies, you are encouraged to write a customized policy that fits your use case better - see Policies, Critics and Agents for more information.

Selection of active actor

Every StructuredEnv is required to implement actor_id(), which returns the ID of the currently active actor. An environment with a single actor, e. g. a flat Gym environment, may return a single-actor signature such as (0, 0). At any time there has to be exactly one active actor ID.

Policy-specific space conversion

Since different policies may benefit from or even require a different preprocessing of their actions and/or observations (especially, but not exclusively, for action masking), Maze requires the specification of a corresponding ActionConversionInterface and ObservationConversionInterface class for each policy. This permits to tailor actions and/or observations to the mode of operation of the relevant policy.

The actor concept and the mechanisms supporting it are thus capable of

representing an arbitrary number of agents;

identifying which policy should be applied for which agent via the provision of

actor_id();representing an arbitrary number of actors with flexible lifecycles that may differ from their environment’s;

supporting an arbitrary nesting of policies (and - in further abstraction - tasks);

selecting actions via the policy fitting the currently active actor;

preprocessing actions and observations w.r.t. the currently used actor/policy.

This allows to bypass the three restrictions laid out at the outset.

Where to Go Next¶

Read about some of the patterns and capabilities possible with structured environments:

The underlying communication pathways are identical for all instances of StructuredEnv. Multi-stepping, multi-agent, hierarchical or other setups are all particular manifestations of structured environments and its actor mechanism. They are orthogonal to each other and can be used in any combination.

- 1

Action masking is used for many problems with large action spaces which would otherwise intractable, e.g. StarCraft II: A New Challenge for Reinforcement Learning.